By Anthony Broadman

Assuming the bottom does not drop out of the legal weed market, and that Tribes are able to begin regulating and selling marijuana within their jurisdictions, how will pot farming revenue be spent? If marijuana is a viable business for Tribes, Tribal governments can expect calls for profits to be “per capped” through per-member distributions. Whether per capitas are good governance is a question for Tribes and their constituents. But the particular treatment of pot per capitas raises new questions about federal trust assets, federal taxation, and whether distributions can provide a new non-taxable trust resource for Tribes and their members.

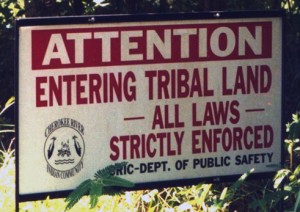

A profitable tribal pot economy requires several leaps of faith and what would formerly have been some wild assumptions. But presuming the reservation market takes shape, Tribes will likely use the revenue from pot cultivation, like all economic development initiatives, to provide essential governmental services to their members. We should expect tribal pot revenue to offset the burdens of legal pot, to be allocated to education, law enforcement, marijuana regulation, anti-drug initiatives, public health efforts, and the other sorts of programs Tribes have long provided within and beyond their territory. But with profits often come calls for per capita distributions.

The general rule is that every cent of your wealth, whether you are a member of an Indian tribe or not, is taxable by the United States. Section 61(a) of the Internal Revenue Code provides that, except as otherwise provided by law, gross income means all income from whatever source derived. Under Section 61, Congress is allowed to tax every “accession[] to wealth.” Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass Co., 348 U.S. 426 (1955). Indians are citizens subject to the payment of these income taxes. Squire v. Capoeman, 351 U.S. 1, 6 (1956).

One narrow exception to this rule is that per capita distributions made from funds the Secretary of the Interior holds in a Trust Account for the benefit of a tribe are generally excluded from the gross income of the members receiving the distributions.

Practically, proceeds from trust assets or trust resources are deposited into a tribal Trust Account for a tribe and that tribe subsequently makes a per capita distribution using funds from that Trust Account. Again, those payments are generally not taxable to members. This is different than the treatment of gaming per capitas. The per capita distribution of gaming revenue is taxable to each recipient.

Could trust assets or resources include marijuana grown by a Tribe on Tribal land? Trust resources means any element or matter directly derived from Indian trust property. 25 C.F.R. § 115.002. In fact, it may not be optional for the United States to accept the revenue from tribal pot cultivation into trust. According to federal trust regulations, the Secretary of the Interior “must accept proceed on behalf of tribes or individuals from the following sources . . . [m]oney directly derived from the . . . use of trust lands.” 25 C.F.R. § 115.702. The IRS has wavered on whether trust per capitas are taxable in the last few years. But after Tribal resistance, provided clarity last year in Notice 2014-17.

The IRS often rejects as trust resources that revenue which may be derived from land but is really mischaracterized business profits. But as for marijuana grown on tribal trust land, which is then harvested and sold by the Tribe in the first instance, the resulting revenue is almost certainly money directly derived from the use of tribal trust land. Indeed, there is no difference between pot and timber except that pot is an illegal schedule I controlled substance.

Whether the Secretary can or would accept proceeds from the sale of marijuana grown on Tribal lands – like it does timber – into trust is a different question. Marijuana remains illegal under federal law and even though the DOJ may not be enforcing marijuana laws, participating in what would effectively be the banking of illegal drug revenue feels like a bridge too far. After all, if they won’t let banks easily accept pot profits, how could the feds themselves deposit such funds? Still, the potential for distribution of pot profits could provide tribes with a new source of non-taxable distribution income for members. That, given the stagnating gaming per capita landscape, is a potential novel benefit as Tribes balance the harms and benefits of the marijuana economy.

Anthony Broadman is a partner at Galanda Broadman PLLC. He can be reached at 206.321.2672, anthony@galandabroadman.com, or via www.galandabroadman.com. Marijuana is illegal under federal law.

ribal sovereign immunity from state action, but also tribal sovereignty and Indian gaming in general. ... Still, tribal governments are nowhere near out of the woods.”

ribal sovereign immunity from state action, but also tribal sovereignty and Indian gaming in general. ... Still, tribal governments are nowhere near out of the woods.”