By Joe Sexton

The core message of Dr. King’s “Letter From a Birmingham Jail” means more in 2026 than it has since the 1960s. Thankfully, he prepared us for this moment, and for America’s confrontation of overbroad and unjust immigration enforcement.

Just as institutions failed initially to meet the moment of the Civil Rights struggle, our institutions now present little in the way of comfort. Even the Supreme Court of the United States has fallen short. In a shadow-docket decision handed down a few months ago, the Court sanctioned these injustices, allowing for racial profiling in immigration detentions. The Court did so without briefing or argument, and without a majority opinion that addresses past precedent, statutes, regulations, and our Constitution.

Even worse, Justice Kavanaugh penned a concurrence that hollows out the 4th Amendment’s protections when it comes to federal immigration enforcement actions against people who do not appear white.

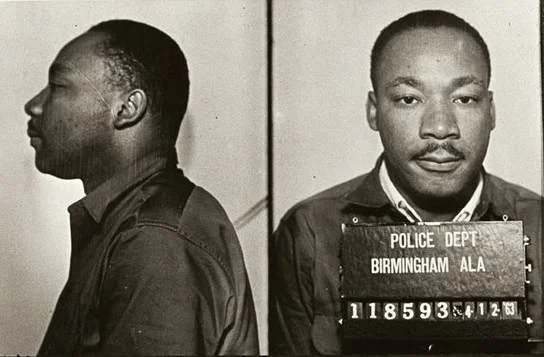

King wrote his 1963 letter while he was jailed for violating a state court order that barred demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama. His letter was a response to a message signed by eight white clergymen, all of whom were from Alabama. In their missive, these clergymen pled with the Black community to stop demonstrating and protesting in Alabama, appealing to “the principles of law and order.” They argued that when “rights are consistently denied” those aggrieved should work “in the courts and in negotiations among local leaders, and not in the streets.”[1] These fellow religious leaders complained of King and other “outsiders” stirring up “such actions as [to] incite hatred and violence,” lecturing those civil rights leaders that “however technically peaceful their actions may be” they do not resolve “our local problems.”

Injustice Is Never Merely Local.

King’s response was unequivocal:

I am in Birmingham because injustice is here . . . I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. . . Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial "outside agitator" idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.[2]

The Roberts Court today is reaffirming the truth of King’s message, and showing us how fragile the progress is that we as a nation made through the leadership of King and the civil rights movement, showing us the way through their peaceful resistance. The clergymen who wrote King did not seem to be writing in bad faith. They were very likely good people who wanted institutional racism to end on the one hand, and peace and tranquility to persist on the other, at the same time. They believed in our justice system and the rule of law.

But King understood that in the absence of resistance our system will not work on its own to root out injustice. It will not stop a state whose leaders are committed to injustice as a means to whatever may be the ultimate end. “We know through painful experience,” King answered the clergymen, “that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed."[3]

The Supreme Court Has Fundamentally Altered 4th Amendment Law To Allow Racial Profiling As A Basis For Extended Detentions Of Lawful Citizens.

For half a century before this year’s decision in Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo this past September, the Supreme Court had been skeptical of law enforcement’s reliance on ethnicity, race, or related factors as grounds for reasonable suspicion to justify arrests, often times throwing out criminal cases where the predicate for the seizure included alleged reasonable suspicion tied to someone’s ethnicity, or some other category that may describe a large category of otherwise innocent people, like speaking Spanish or having brown skin.[4]

But Justice Kavanaugh's concurrence in Vasquez Perdomo provided a new framework—the "Kavanaugh Rule”—for immigration stops that accepts "apparent ethnicity," Spanish or accented English, presence at certain locations (like day‑labor corners or car washes), and low‑wage work as "relevant factors" that together can justify an interior immigration stop and seizure.[5]

In effect, the Kavanaugh Rule blesses a suspicion template that sanctions sweeping immigration dragnets in non-white communities, targeting people of color directly because they are not white.[6] Kavanaugh reassures us that these are only "brief investigative stops" and that "individuals who are U.S. citizens or otherwise lawfully present will be promptly released once their status is ascertained," portraying the intrusion as minimal and easily corrected.[7]

Kavanaugh, however, ignores the reality of what was happening on the ground at the time he penned his concurrence,[8] and he disregards the potential for abuses depending on how the Trump government would leverage the Kavanaugh Rule.[9]

Justice Sotomayor’s dissent warned that under the new Kavanaugh Rule, reasonable suspicion justifying arrest may be based on factors that describe millions of United States citizens and lawful residents whose only 'suspicion' is that they live and work while looking or sounding ‘foreign.’[10] The factors which may now form reasonable suspicion to detain someone “describe a very large category of presumably innocent” people and in practice sweep in “anyone who looks Latino, speaks Spanish, and appears to work a low‑wage job."[11]

The dissent forecasted that the Kavanaugh Rule effectively creating "a second‑class citizenship status."[12] The dissent was immediately proven right. And we find ourselves once again in a place where innocent brown people—including Indigenous people, astonishingly—may find themselves in jail for extended periods merely because of the color of their skin, the language they speak, or the work they do.

Under the Kavanaugh Rule, DHS is now at liberty to mark entire classes of non‑white people as presumptively suspect, and licenses militarized federal forces to violate those people’s human and constitutional rights, but only for “brief” periods in Kavanaugh’s view. What we’ve seen emerge in the wake of Vasquez Perdomo and the Kavanaugh Rule shows race and ethnicity-based detentions that go beyond any reasonable definition of “brief.”

A December 2025 report of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations documented 24 U.S. citizens whom ICE or CBP illegally detained or deported.[13] Of 22 citizens interviewed for the report, the government held seven for more than 24 hours, and several were held between 48 and 96 hours.[14] Examples include:

· George Retes, a disabled U.S. Army veteran, pulled from his car and detained for more than three days despite his citizenship.

· Javier Ramirez, a diabetic U.S. citizen father, beaten, shackled, and jailed for over 96 hours despite having proof of citizenship on his person.

· Andrea Velez, a citizen held over 48 hours despite repeatedly asserting citizenship and having identification in her bag.

· Chanthila Souvannarath, with a long‑standing citizenship claim, deported to Laos in 2025 in direct defiance of a federal court order—ICE simply ignored the judiciary.[15]

Even producing proof of citizenship, or offering to, does not reliably end these encounters.[16] In the real world, people of color confronted by armed agents cannot rely on the promise of a 'quick clarification' when officers already view them as presumptively deportable:

· Javier Ramirez told agents he had valid U.S. ID and a passport in his pocket; an agent allegedly said "just get him, he's Mexican," and he was still detained four days.[17]

· Leonardo Garcia Venegas, a U.S. citizen, was twice detained even after presenting an Alabama STAR ID—a document by law issued only to citizens—which agents dismissed as "fake."[18]

· In Minneapolis, Mubashir Khalif Hussen, a U.S. citizen, was put in a headlock by plain‑clothes ICE agents while walking to lunch; he told them he was a citizen and offered to show his passport but was held for hours before anyone checked it.[19]

· At a Minneapolis Target in January 2026, video shows two employees violently tackled and handcuffed inside the store by federal officers; state officials later confirmed both were U.S. citizens; at least one of these victims insisted he was a citizen as he was dragged away.[20]

These are not brief investigative stops. They are prolonged, sometimes violent warrantless seizures. This is precisely the kind of abuse the Fourth Amendment was intended to protect against.

DHS Is Targeting First Americans.

And now because being a person of color may be used as a predicate for warrantless arrests and detentions, DHS is targeting Indigenous people. The Native American Rights Fund (NARF) describes ICE abducting Tribal members—"the first peoples of this land”—based solely on racial profiling.[21] We increasingly hear of ICE showing up at Tribal casinos and enterprises to question and detain Indigenous workers whose citizenship is not in doubt, but whose appearance fits the immigration "profile" the Supreme Court has licensed ICE to target.[22] Knowing that ICE lacks jurisdiction over citizens is little comfort to first peoples who are detained and justifiably afraid.

This administration would no doubt dismiss any violence against a detainee as warranted. So resisting appears to carry more risk than it ever has. Possession of a claim against the United States for violating one’s rights is little comfort to the dead. King insisted that "an unjust law is a code that a numerical or power majority compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself," and this is exactly what the Kavanaugh Rule represents: a Fourth Amendment that functions fully for whites and the powerful, but only conditionally, if at all, for communities of color.[23] The problem, as King noted, is that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”[24]

We Must All Work For Change To End This Regression.

King warned that the greatest stumbling block might not be the open racist, but the "white moderate who is more devoted to 'order' than to justice."[25] A Supreme Court that privileges federal "immigration sweeps" and "order" over the explicit, documented violations of the Fourth Amendment against non‑white citizens is reenacting that very dynamic from the bench.

This is regression, aiming our trajectory backwards to the dark days of genocide and segregation. Allowing armed federal agents to detain people inside our borders because they are brown, Indigenous, Somali, or otherwise marked as "foreign," and then excusing extended detentions of citizens as necessary to preserve law and order moves the United States back toward an era when full rights were reserved for whites and men, and everyone else's liberty was subject to conditions and exceptions.

By normalizing racialized dragnets and hollowing out Fourth Amendment protections for entire classes of people, we are undermining King’s work. The movement King catalyzed in the 20th century aimed to dismantle this oppression through non-violent resistance. To stop this regression, I believe we all need to resist, even those of us privileged enough to be safe from the terror we are watching visited upon our non-white neighbors. We must take King’s final public words to heart and turn them into action; words he gave us in a speech the night before he was gunned down in Memphis:

If I lived in China or even Russia, or any totalitarian country, maybe I could understand some of these illegal injunctions. Maybe I could understand the denial of certain basic First Amendment privileges, because they hadn't committed themselves to that over there. But somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech. Somewhere I read of the freedom of press. Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for right. And so just as I say, we aren't going to let dogs or water hoses turn us around, we aren't going to let any injunction turn us around. We are going on.

We need all of you.[26]

Joe Sexton is a partner at Galanda Broadman, PLLC. Joe’s practice focuses on tribal sovereignty issues, including complex land and environmental issues, and economic development matters. He is a Unites States Marine Corps veteran. He can be reached at (509) 910-8842 and joe@galandbroadman.com.

[1] Letter from clergymen to King, found here.

[2] Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter From A Birmingham Jail.”

[3] Id.

[4] See e.g., United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, 422 U.S. 873, 885–87 (1975) (“Mexican appearance” alone cannot justify stopping a car; “large numbers of native-born and naturalized citizens have the physical characteristics identified with Mexican ancestry.”); see also Reid v. Georgia, 448 U.S. 438, 441 (1980) (per curiam) (Court declines to find reasonable suspicion based on “circumstances [that] describe a very large category of presumably innocent travelers who would be subject to virtually random seizures . . .”).

[5] Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo, 606 U.S. ___ (2025)(Kavanaugh, J., concurring). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/25a169_5h25.pdf (Kavanaugh, J., concurring); see also "Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Racial Proxies," SCOTUSblog, September 24, 2025, https://www.scotusblog.com/2025/09/justice-brett-kavanaugh-and-racial-proxies/.

[6] The Supreme Court Decision on ICE and Racial Profiling, Explained," The New York Times, September 8, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/08/us/politics/supreme-court-immigration-racial-profiling.html; Native American Rights Fund, "NARF Statement on Unlawful ICE Activity," January 15, 2026, https://narf.org/narf-statement-ice/; "Minnesota Legislators Confirm Minneapolis Police Conduct ICE Sweeps," NPR, November 5, 2025, https://www.npr.org/2025/11/05/nx-s1-5598373/npr-fact-checks-kristi-noem-on-ice-detaining-us-citizens.

[7] Id.

[8] “The concurrence relegates the interests of U. S. citizens and individuals with legal status to a single sentence, positing that the Government will free these individuals as soon as they show they are legally in the United States . . . That blinks reality. Two plaintiffs in this very case tried to explain that they are U. S. citizens; one was then pushed against a fence with his arms twisted behind his back, and the other was taken away from his job to a warehouse for further questioning.” Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo, 606 U.S. ___, ___ (2025) (Sotomayor, J., dissenting). In the post-Kavanaugh-Rule America, even those brief detentions are mild by comparison to what is happening to many brown people who are being ripped from their vehicles and workplaces, violently restrained and thrown into the backs of unmarked SUVs, and driven to detention centers where they are likely searched, have their valuables seized, and thrown into a cell without any ability to contact family or legal counsel, and if they’re fortunate, released hours later without charges because ultimately they did nothing wrong. They were merely non-white and existing in America.

[9] "Target Employees Detained by Federal Officers Were U.S. Citizens," KCCI-8, YouTube, January 12, 2026, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mE9NmlNeiIQ; Native American Rights Fund, "NARF Statement on Unlawful ICE Activity," January 15, 2026, https://narf.org/narf-statement-ice/; Pear, Robert, "ICE Barbie Warns Americans Must Be Prepared to Prove Citizenship," The Daily Beast, January 15, 2026, https://www.thedailybeast.com/ice-barbie-warns-americans-must-be-prepared-to-prove-citizenship/.

[10] See Vasquez Perdomo, 606 U.S. ___, ___ (2025) (Sotomayor, J., dissenting).

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, "Unchecked Authority: How ICE and CBP Illegally Detained and Deported U.S. Citizens," December 8, 2025, https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025.12.8_ICE-Report-revised-FINAL.pdf.

[14] Id.

[15] National Immigrant Project of the National Lawyers Guild, "ICE Deports Man Claiming U.S. Citizenship to Laos Despite Federal Court Order," October 28, 2025, https://nipnlg.org/news/press-releases/ice-deports-man-claiming-us-citizenship-laos-despite-federal-court-order.

[16] Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, "Unchecked Authority," supra note 13.

[17] Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, "Unchecked Authority," supra note 13.

[18] Id.

[19] ICE Agents Wrongfully Detained US Citizen, Minneapolis Mayor Says," CBS Minnesota, December 10, 2025, https://www.cbsnews.com/minnesota/news/minneapolis-leaders-say-us-citizen-was-wrongfully-arrested-by-ice-agents/ ; ACLU, "ACLU Sues Federal Government to End ICE, CBP's Practice of Suspicionless Stops, Warrantless Arrests," January 14, 2026, https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/aclu-sues-federal-government-to-end-ice-cbps-practice-of-suspicionless-stops-warrantless-arr.

[20] "Target Employees Detained by Federal Officers Were U.S. Citizens," KCCI-8, YouTube, January 12, 2026, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mE9NmlNeiIQ.

[21] Native American Rights Fund, "NARF Statement on Unlawful ICE Activity," supra note 6.

[22]Native Nations Mobilize Against ICE Targeting and Profiling, UNDERSCORE NEWS (Feb. 10, 2025), https://www.underscore.news/justice/federal-policy/native-nations-mobilize-against-ice-targeting-and-profiling/.; see also Native Americans Are Being Swept Up by ICE in Minneapolis, Tribes Say, WASH. POST (Jan. 15, 2026), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2026/01/15/native-americans-ice-minneapolis/.

[23] King, "Letter from a Birmingham Jail," supra note 1

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Martin Luther King, Jr., I’ve Been to the Mountaintop (Apr. 3, 1968), in AM. RHETORIC, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkivebeentothemountaintop.htm